Title & author

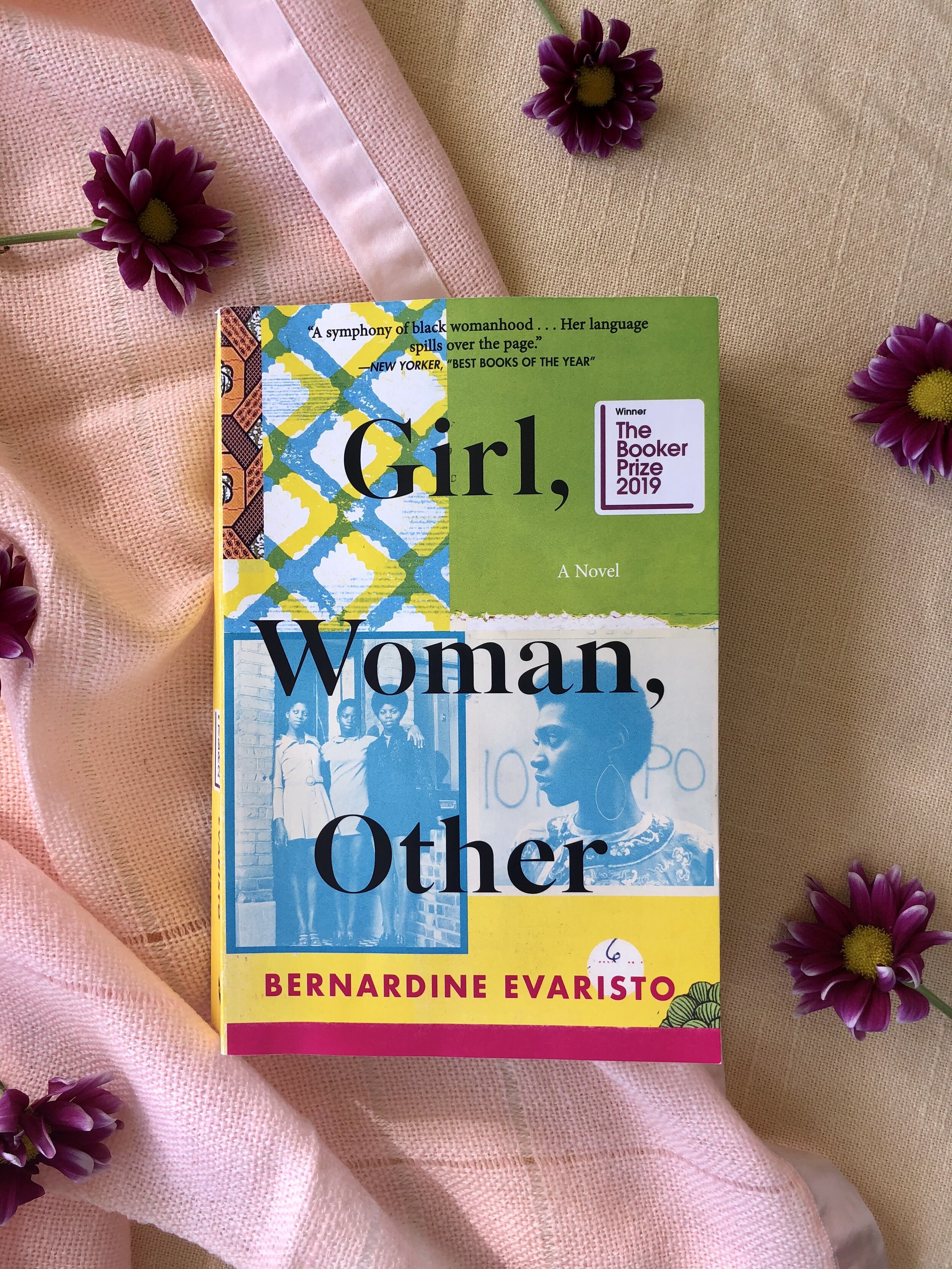

Girl, Woman, Other by Bernardine Evaristo

Synopsis

Girl, Woman, Other’s 12 varying perspectives each depict a different exploration of a Black woman or nonbinary individual’s identity within a white, western space, each character working to transcend or combat societal expectations. Yet all the while, the story is about these individuals, and never the society that attempts to limit them.

Who should read this book

Fans of The Night Watchman

What we’re thinking about

How experimental writing impacts our reading

Trigger warning(s)

Physical violence, sexual violence, substance abuse, self-harm, slurs, abortion, abandonment, sexim, mental health, racism, transphobia, homophobia

When we say a title is untraditional, or that it’s written in an experimental way, what exactly does that mean? What are we comparing the title against? What expectations and assumptions does that subsequently mean we are placing upon a story, and how do those assumptions shape our reading before we even open the book? Author Bernardine Evaristo herself has called Girl, Woman, Other (Black Cat, 2019) “experimental” in its writing style, and her choices in many ways mirror the challenges her 12 narrators face. As Black women and nonbinary folks living in a white, western society, that society places white, western expectations and assumptions onto them. In an interview, Evaristo details the gaps in the UK’s publishing industry (many of which are issues within the US’s industry as well), noting she wrote this story wanting to make as many Black women as visible as possible. Girl, Woman, Other’s 12 varying perspectives each depict a different exploration of identity within a white, western space, each character working to transcend or combat societal expectations. Yet all the while, the story is about these individuals, and never the society that attempts to limit them.

In Evaristo’s chapter “Carole,” the narrator reveals how she survives and hopes to succeed in a society dictated by whiteness. Working in finance, Carole “will stride up to the client, shake his hand firmly (yet femininely), while looking him warmly (yet confidently) in the eye and smiling innocently, and delivering her name unto him with perfectly clipped Received Pronunciation, showing off her pretty (thank-god-they’re-not-too-thick) lips…” (Evaristo, 117). Carole narrates the everyday racism and sexism a Black woman experiences: she must both work to appear the ‘perfect balance’ of professional and womanly, and also work to prevent others from seeing her as stereotypically ‘Black.’ It’s a form of code switching — changing who she is around white individuals to protect herself. However for Carole, that switch rarely ever changes. Even when she’s “furious” at individuals who “wanted to undermine her hard-won professionalism,” she must “politely extricate herself” (118). Carole cannot take off her mask, even in her home with her fiance. There are few brief moments we witness what’s underneath: Only “while dancing/for herself.../nobody watching/nobody judging” and through flashbacks to her childhood and sexual assault (141). “Mama...Mama...clever Mama,” she repeats at the start of three paragraphs, though at every other point in the chapter she refers to her mom as “mother” (121). Evaristo allows us to see just enough of Carole to know she’s hiding who she is, and that she has no choice but to hide who she is if she wants to succeed in the life she’s created for herself. And, importantly, she shows us why Carole has created this life.

On the other end of the spectrum is Amma. A theatre director, Amma at a young age was “disillusioned at being put up for parts such as a slave, servant, prostitute, nanny or crim” (6). Tired of the racist tropes she’s repeatedly assigned to as an actress, Amma instead decides to carve her own path. With her friend Dominique, she creates a production company “on their own terms” (14). Opposite from Carole, Amma attempts to succeed by rejecting the limitations placed on her by white society in a different way by focusing her work on Black women and stories. But when her play makes it into a large theatre instead of smaller community ones, she’s accused of dropping her “‘principles for ambition’” and being “‘establishment with a capital E’” (33).

And thus the ever-present paradox: how does one carve their way through a society rigged against them that seems destined to evolve to stay rigged against them? Carole is trapped— she can never be herself. And for Amma to achieve her career goals, she still must win over critics and the public, so to an extent she must win over white society. No matter what, their survival is dependent upon white society’s approval and at the whim of white society’s gatekeeping.

In choosing to use little punctuation and capitalization throughout the novel, Evaristo not only challenges our assumptions but also knocks us off-balance. Punctuation helps readers know how to react, but in absence of that, we’re left to our own interpretations. “I be your mama/ now and forever/ never forget that, abi?” (158). Without punctuation, from the start we are forced to feel like visitors, entering an unfamiliar world. Our privilege, the belief we know all, is removed. In its place, all we can do is listen, think, and absorb, and ask ourselves how we might work to create a society that is truly equitable and accessible to all.

“Something in her realized that her prettiness was supposed to make her compliant, and when she wasn’t, when she rebelled, she was letting down all those invested in her being adorable.”

Join in

Contribute your thoughts by using the “Leave a comment” button found underneath the share buttons below. Answer one of these questions, ask your own, respond to others, and more.

How does the experimental writing in Girl, Woman, Other shape our reading?

Which perspective has stayed with you? Why?

Please note that all comments must be approved by the moderator before posting. We reserve the right to deny offensive or spam-related commentary. And, for the wellbeing of our BIPOC, LGBTQIA+, and/or disabled-identifying community members, please respect the personal capacity to address questions on certain topics. We encourage you to search for the answer in a great book or online instead. Thank you!