Title & author

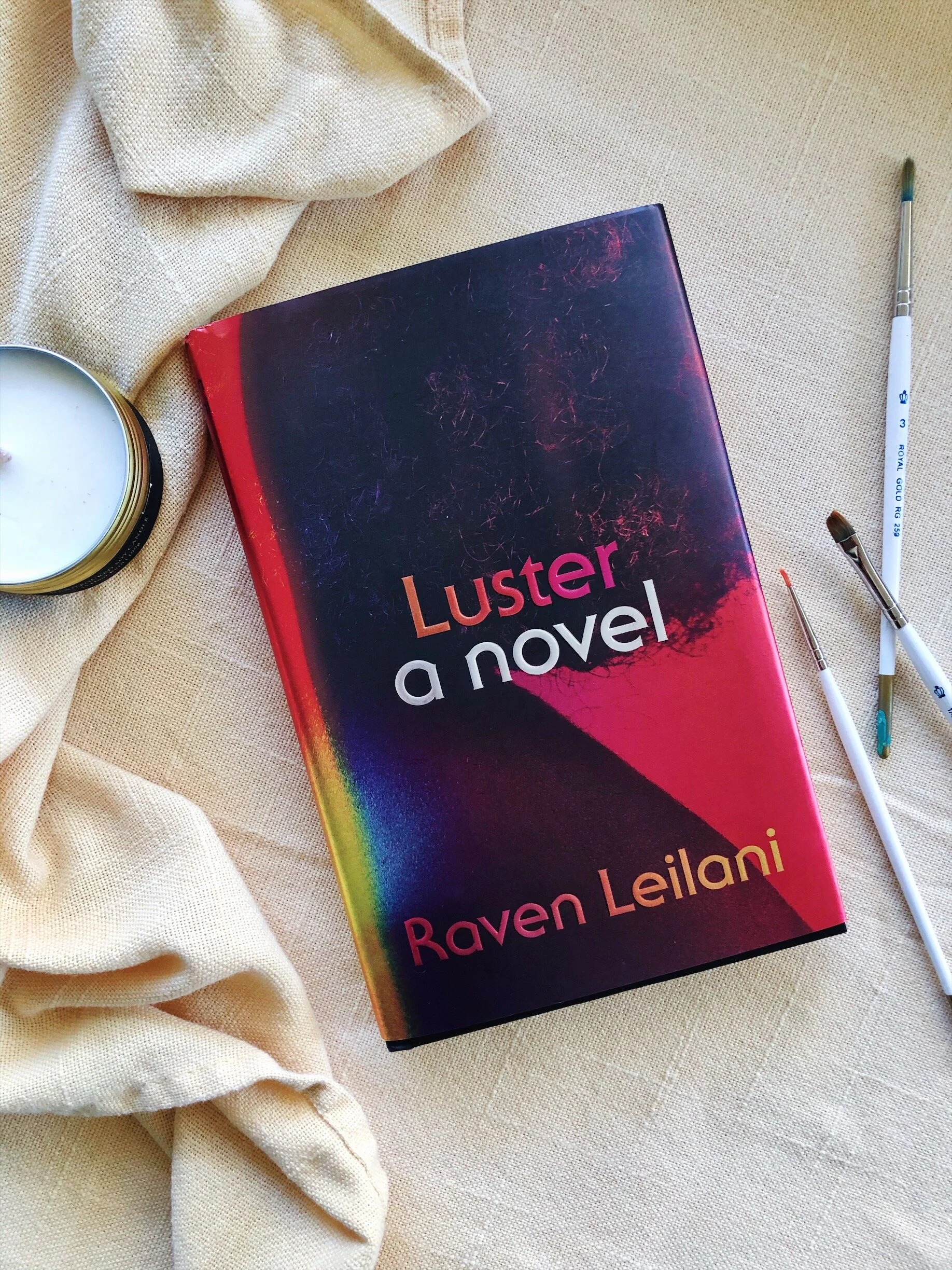

Luster by Raven Leilani

Synopsis

Throughout Luster, as Edie navigates unconventional relationships, she explores the physicality of bodies— through sex, painting, and relationships. Using Edie’s involvement with Eric and Rebecca, a married couple, as a canvas, Leilani’s masterful conveyance of train of thought and imagery create a vivid depiction of a young woman’s hunt for identity through art.

Who should read this book

Fans of Such A Fun Age and Everything I Never Told You

What we’re thinking about

How sex can be considered as an artform

Trigger warning(s)

Physical violence, slurs, abortion, abandonment, sexism, mental health, racism

“The first time we have sex,” Raven Leilani’s protagonist Edie begins, “we are both fully clothed, at our desks during working hours, bathed in blue computer light” (Leilani, 3). The opening line of Luster (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020) perfectly sets the stage for the novel. Sitting in a different building than the man she’s chatting online with, Edie does not limit her perception of sex to intercourse. Instead, sex becomes about the bodies, the people and their identities. And throughout Luster, as Edie navigates unconventional relationships, this exploration of bodies continues. In Edie’s initial involvement with Eric and later with his wife, Leilani’s masterful conveyance of train of thought and imagery create a vivid depiction of a young woman’s hunt for identity through art.

Central to Edie’s story is her exploration of the human body and identity, but as a Black woman, she faces constant criticism from both strangers and peers. “There are men who are an answer to a biological imperative, whom I chew and swallow, and there are men I hold in my mouth until they dissolve” (27). Edie sleeps with some men simply out of sexual cravings, unafraid to fill that need, and some she hangs onto, longing for company. However, all of these men have their own identities: “Hamish from contracts...with that blue streak in his hair” and “Tyrell…[with] dark, reflective eyes” and “Arjun...with his slick black hair and cartoon villain forearms” (24-25). She explores their bodies just as she does her own, noting their corporal features and characteristics with particular details rooted in color, like an artist might.

However, unlike the men she sleeps with at work, she is known as the “office slut” (23). While her male coworkers go unpunished for their sexual acts, Edie is cast out by the office and eventually fired. This is even further emphasized by Edie’s relationship with Eric, a man in “new territory. Not simply to be on a date with someone who is not his wife and decades younger, but to be out with a girl who happens to be black” (7). The racism Edie faces as a result of her relationship with Eric is not the sole focus of Leilani’s novel, rather the environment, holding influence over her experience and journey. “I cannot be the first black girl a white man dates. I cannot endure the nervous renditions of backpacker rap, the conspicuous effort to be colloquial, or the smugness of pink men in kente cloth” (7-8).

But yet this exploration remains critical to Edie. After not painting for two years, she picks up her paints once more, “work[ing] with the paint, let[ting] the acrylic dry, and when it isn’t right [reworking] it again” (17). Inspired by a look on Eric’s face during their first date, Edie begins to work on depicting human anatomy, a skill she’s been told she lacks. And throughout the story, she continues to do so, first with Eric, and later with self-portraits, dead bodies, and even Eric’s wife, Rebecca.

Leilani’s imagery itself is what creates this sense of exploration, the exposé on identity. “All my joy is underneath the palette knife, the folds of the body more pronounced and so more fun to paint, the palette overwhelmingly Caucaisain, and so a little tedious, though inside the body there is room to experiment with blues and dark, cool reds” (188). The ongoing train of thoughts and use of metaphorical imagery throughout the novel create a captivatingly illustrative portrait of not just the bodies she paints, but of Edie as well. And are we to recognize the decision to have Edie work so closely with the human body as one filled with meaning? Historically, our society built upon white supremacist values has not valued Black women’s bodies as their own; whether during enslavement and still today, as white, racist beauty standards both critique and worship Black women’s appearance, Edie’s act to master human art form, to have control over not just her body, but the body of anyone she decides to paint, might be viewed as an act of rebellion, an act of taking back.

The richness and subtle complexity of Luster is embedded into every page, from what we learn of Edie’s childhood, youth, and early adulthood, to what she imagines others in her life to have experienced. And though there are questions that go unanswered by the novel’s last page, they never feel like loose ends. Instead, they feel like prompts, ones that further the incomplete picture Edie works on. They urge the reader to understand that the story is ongoing, not simply finished when the book ends. Edie’s exploration of self cannot be rushed, cannot be determined by a mere 200+ pages of a novel. Although this time frame can help us understand who she might currently be, it can only do so much to help us understand who she is becoming.

“I am inclined to pray, but on principle, I don’t. God is not for women. He is for the fruit. He makes you want and he makes you wicked, and while you sleep, he plants a seed in your womb that will be born just to die.”

Join in

Contribute your thoughts by using the “Leave a comment” button found underneath the share buttons below. Answer one of these questions, ask your own, respond to others, and more.

From the cover to Edie’s paintings and view of the world, color plays a large part in Luster. How does Leilani’s use of color contribute to the story and/or create something on its own?

What do you make of Edie and Rebecca’s relationship? What does it teach us about Edie?

Please note that all comments must be approved by the moderator before posting. We reserve the right to deny offensive or spam-related commentary. And, for the wellbeing of our BIPOC, LGBTQIA+, and/or disabled-identifying community members, please respect the personal capacity to address questions on certain topics. We encourage you to search for the answer in a great book or online instead. Thank you!